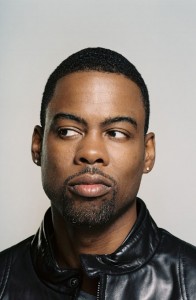

Chris Rock has become one of the most popular comedians in the world and, while there is no doubt he’s got great talent, his brilliance also comes from his approach to developing his ideas. The routines he rolls out on his global tours are the output of what he has learned from thousands of “little bets,” nearly all of which fail.

Chris Rock has become one of the most popular comedians in the world and, while there is no doubt he’s got great talent, his brilliance also comes from his approach to developing his ideas. The routines he rolls out on his global tours are the output of what he has learned from thousands of “little bets,” nearly all of which fail.

When beginning to work on a new show, Rock picks venues where he can experiment with new material in very rough fashion. In gearing up for his latest global tour, he made between 40 and 50 appearances at a small comedy club called Stress Factory in New Brunswick, New Jersey, not far from where he lives. In front of audiences of say 50 people, he will show up unannounced, carrying a yellow legal note pad with joke ideas scribbled on it. “It’s like boxing training camp,” Rock told the told the Orange Country Register.

When people in the audience spot him, they start whispering to one another. As the wait-staff and other comedians find places to stand at the sides or back, the room quickly fills with anticipation. But he won’t launch into the familiar performance mode his fans describe as “the full preacher effect,” when he uses animated body language, pitchy and sassy vocal intonations, and erupting facial expressions. Instead, he will talk with the audience in an informal, conversational style with his notepad on a stool beside him. He watches the audience intently, noticing heads nodding, shifting body language, or attentive pauses, all clues about where good ideas might reside.

In sets that run around 45 minutes, most of the jokes fall flat. His early performances can be painful to watch. Jokes will ramble, he’ll lose his train of thought and need to refer back to his notes, and some audience members sit with their arms folded, noticeably unimpressed. The audience will laugh about his flops – laughing at him, not with him. Often Rock will pause and say, “This needs to be fleshed out more if it’s gonna make it,” before scribbling down some notes. He may think he has come up with the best joke ever, but if it keeps missing with audiences, that becomes his reality. Other times, a joke he thought would be a dud will bring the house down. According to fellow comedian Matt Ruby, “There are 5-10 lines during the night that are just ridiculously good. Like lightning bolts. My sense is that he starts with these bolts and then writes around them.”

For a full routine, Rock tries hundreds (if not thousands) of preliminary ideas, out of which only a handful will make the final cut. A successful joke often has six or seven parts. With that level of complexity, it’s understandable that even a comedian as successful as Chris Rock wouldn’t be able to know in advance which joke elements and which combinations will work. This is true for every stand-up comedian, including the top performers we tend to perceive as creative geniuses, like Rock or Jerry Seinfeld. It’s also true for comedy writers. The staff of writers for the humor publication The Onion, known for its hilarious headlines, propose roughly 600 possibilities for 18 headlines each week, a 3% success rate. “You can sit down and spend hours crafting some joke that you think is perfect, but a lot of the time, that’s just a waste of time,” Ruby explains. This may seem like an obvious problem, but it’s a mistake that rookie comedians make all the time.

By the time Rock reaches a big show – say an HBO special or an appearance on David Letterman – his jokes, opening, transitions, and closing have all been tested and retested rigorously. Developing an hour-long act takes even top comedians between six months and a year. If comedians are serious about success, they get on stage every night they can, especially when developing new material. They typically do so at least five nights per week, sometimes up to seven, and sweat over every element and word. And the cycle repeats, day in, day out.

Most people are surprised that someone who has reached Chris Rock’s level of success still puts himself out there in this way, willing to fail night after night. But Rock deeply understands that ingenious ideas almost never spring into people’s minds fully formed; they emerge through a rigorous experimental discovery process. As Matt Ruby says of Rock’s performances, “I’m not sure there’s any better comedy class than watching someone that good work on material at that stage. More than anything, you see how much hard work it is. He’s grinding out this material.”